Quantifying the Climatic Impact of Anthropogenic Actions and the Imperative for Carbon Pricing Mechanisms

Executive Summary

This report aims to introduce an approach to tackling the complex issue of climate change and global temperature rise. It provides evidence that anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions from industry are leading to increased temperatures and climate change. Although the evidence is clear there is still a lack of progress being made in carbon abatement solutions. This report outlines the economic theory and history of pricing in negative externalities such as pollution and explores the past and current policy that has been implemented. There has been evidence of carbon pricing mechanisms leading to a reduction in carbon emissions. A cap–and-trade model can allow policy makers to implement a “cap” or limit on the quantity of carbon emissions and allow firms to trade allowance permits to reach an optimal quantity and price on carbon allowances. This has been supported by economic theory and proven to lead to the most efficient allocation of permits and the highest level of emissions abatement. This report highlights the need to incorporate environmental impacts into all decision making and pleads for international regulators to implement some form of carbon pricing mechanism to ensure firms internalize their impacts on the environment. It is clear that all stakeholders are becoming increasingly concerned with the change in climate and the need to have transparent communication and effective pollution pricing mechanisms. As the field sustainability continues to rapidly expand we hopefully will see more implementation of policies and frameworks such as this as well as increased innovation.

1. Introduction

In 1987, the United Nations Brundtland Commission defined sustainability as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.''1 This essentially means meeting our current needs without jeopardizing future generations ability to meet theirs. Unfortunately if we continue to exploit natural resources, the livelihoods of our current future generations may be comprimised. As the effects of climate change have reached the present day, many countries have begun to take action. The UN has been a key driver over the past few decades in building international collaboration and setting standards for other countries to strive towards. In 2015 the UN released its 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and with it 17 SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals). These goals shared a blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future.2 These range from hunger, clean water, inequality, poverty, and climate action. In our analysis of carbon emissions and climate change we will be focusing on goal #13 Climate Action. In order to reach the goals outlined in goal 13’s indicators, such as “Improve education, awareness-raising and human and institutional capacity on climate change mitigation, adaptation, impact reduction and early warning” we will need to develop a strong systems thinking approach. Systems thinking is a way of making sense of the complexity of the world by looking at it in terms of wholes and relationships rather than by splitting it down into its parts.3 This can be a valuable tool when discussing complex climate topics, as there are many things at play when setting climate policy or developing protocols. As we transition to a low carbon economy there needs to be defined collaborations and partnerships to reach net zero targets, and systems thinking can be a holistic approach to improve value chains. When developing solutions to address problems as large as climate change it is necessary to use systems thinking to develop positive feedback looks in all parts of the system. This includes individuals, organizations, governments, countries, and international regimes. As carbon emissions and greenhouse gasses have been proven to directly impact global temperature rise, there have been many methodologies which we will explore. These include carbon footprinting, negative environmental externalities, carbon pricing mechanisms, and the social cost of carbon. These variables can allow us to measure the negative environmental impacts of the system. Once measured and quantified, this will allow businesses and individuals to evaluate their decision making with this question in mind, “what is the environmental cost of this action?”. Hopefully, this will lead to a decrease in human-related activities that cause environmental harm and more organizations working towards protecting our planet.

2. The Problem

2.1 Global temperature rise is causing our climate to change

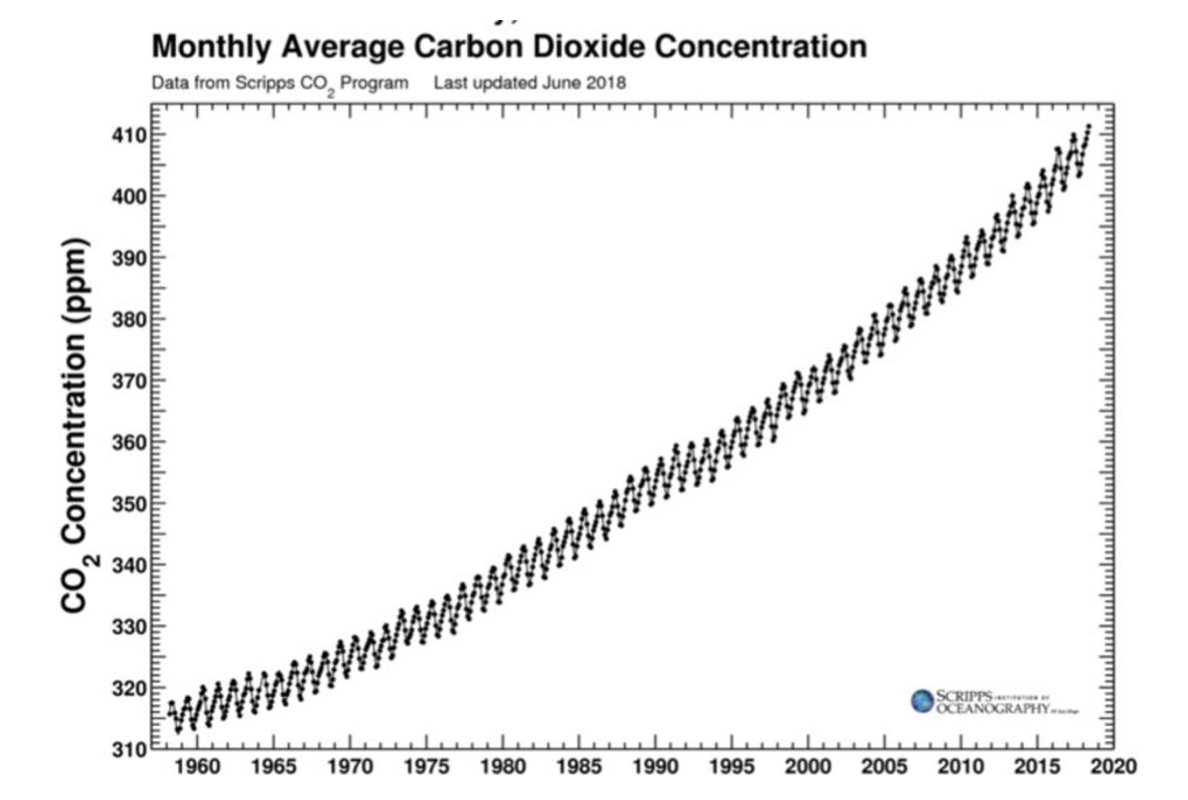

In 2023 there were 28 extreme weather events, costing the US over 92.8 billion dollars. These weather events destroyed homes and cities, and killed 492 innocent citizens—the 8th most disaster-related fatalities for the contiguous U.S. since 1980.4 Global temperatures have risen 1.1 degrees celsius from 1901-2020. This has already impacted our planet and led to record-breaking 4 heat waves on land and in the ocean, drenching rains, severe floods, multiyear-long droughts, extreme wildfires, and widespread flooding during hurricanes are all becoming more frequent and more intense events.5 This is mostly due to the industrial revolution and increased burning of fossil fuels, deforestation, and agricultural practices. Greenhouse gasses trap energy from the sun in the earth's atmosphere causing an increase in global temperatures. This relationship is commonly known as the “greenhouse effect”. Similar to how a greenhouse traps heat for plants to grow, the greenhouse gasses in the earth atmosphere heat up our planet. The first documented evidence was found in 1938 when a steam engineer named Guy Stewart Callendar decided to take a break from his day job and began painstakingly collecting records from 147 weather stations across the world. Doing all his calculations by hand, he discovered that global temperatures had risen 0.3°C over the previous 50 years.6 Just two decades later in 1958 Dr. Keeling began taking measurements of C02, which led to a major discovery in the 20th century, the Keeling Curve. This shows the monthly average CO2 concentration in ppm.

2.2 Impact of Global temperature

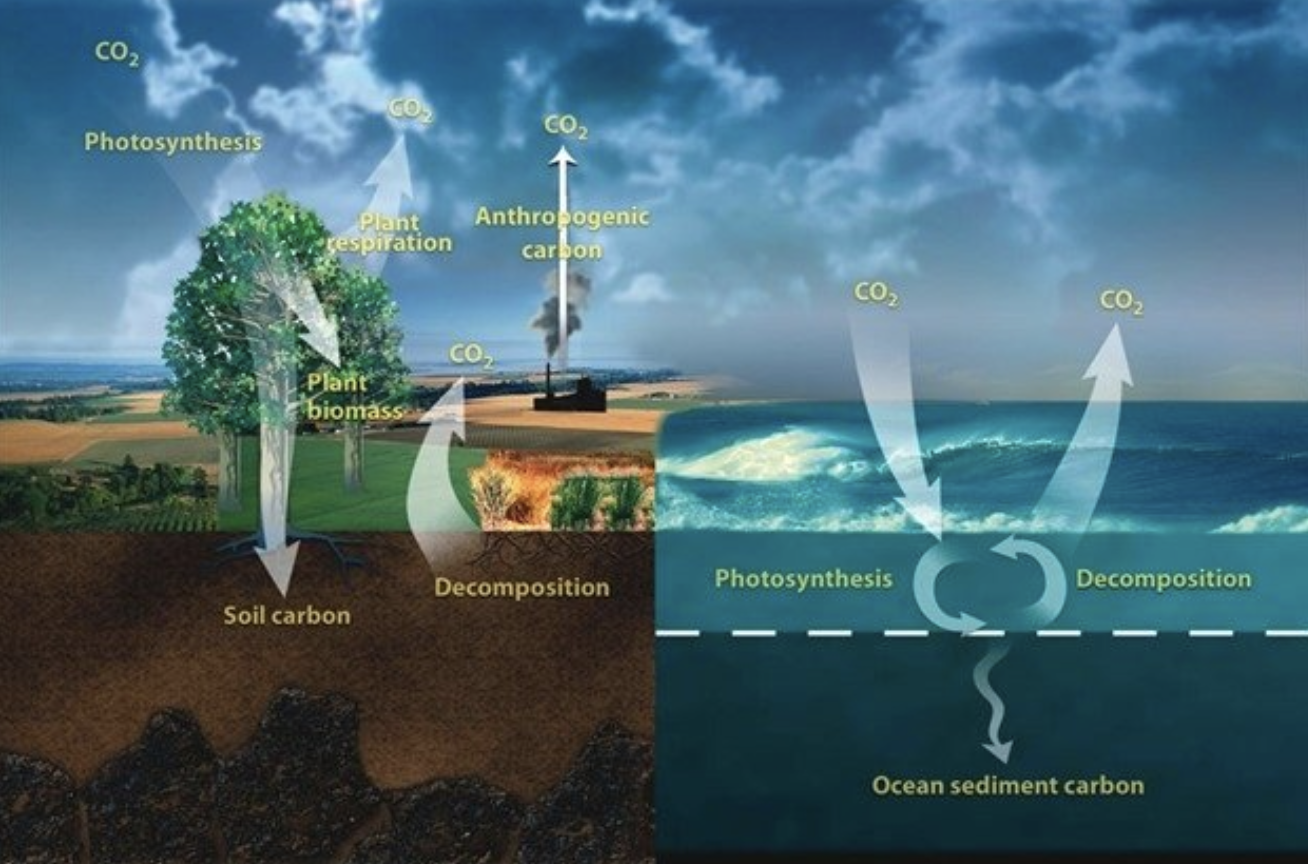

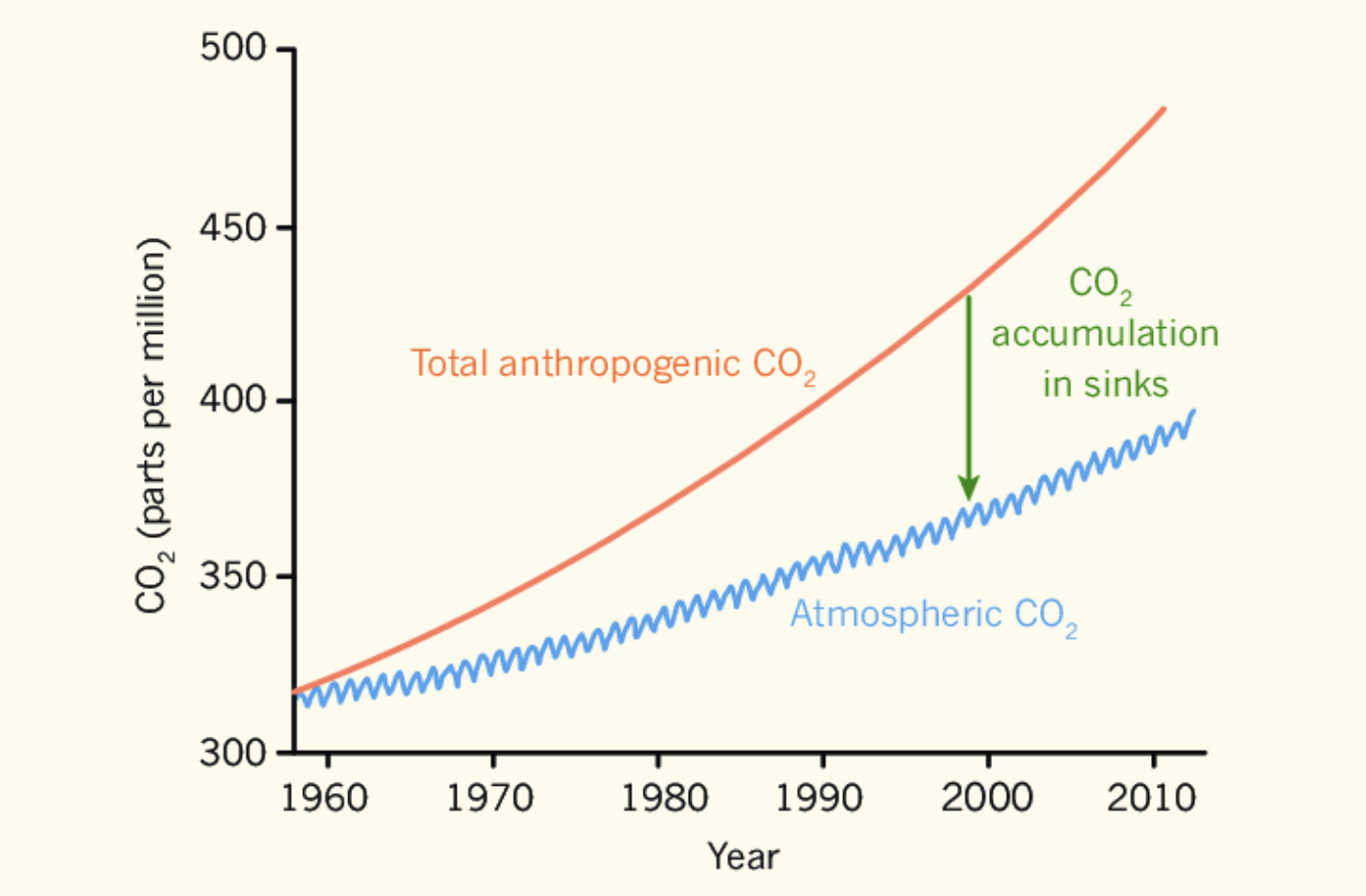

The impacts of this rise in CO2 concentration have been serious. Climate change has impacted the health and well-being of billions of people worldwide. The increased concentration has also led to major environmental impacts that have led to melting ice caps, biodiversity loss, extreme weather events, ocean acidification, and major ecosystem disruptions. Human intervention has led to a disruption in the carbon cycle, which is responsible for balancing our global climate and ecosystem. The carbon cycle is the process that moves carbon between plants, animals, and microbes; minerals in the earth; and the atmosphere.7 Figure 2.2 shows all the carbon sources and 5 “carbon sinks” which sequester carbon from the atmosphere. Another key element of the diagram is “anthropogenic carbon” which is a carbon source that is directly from human activity.

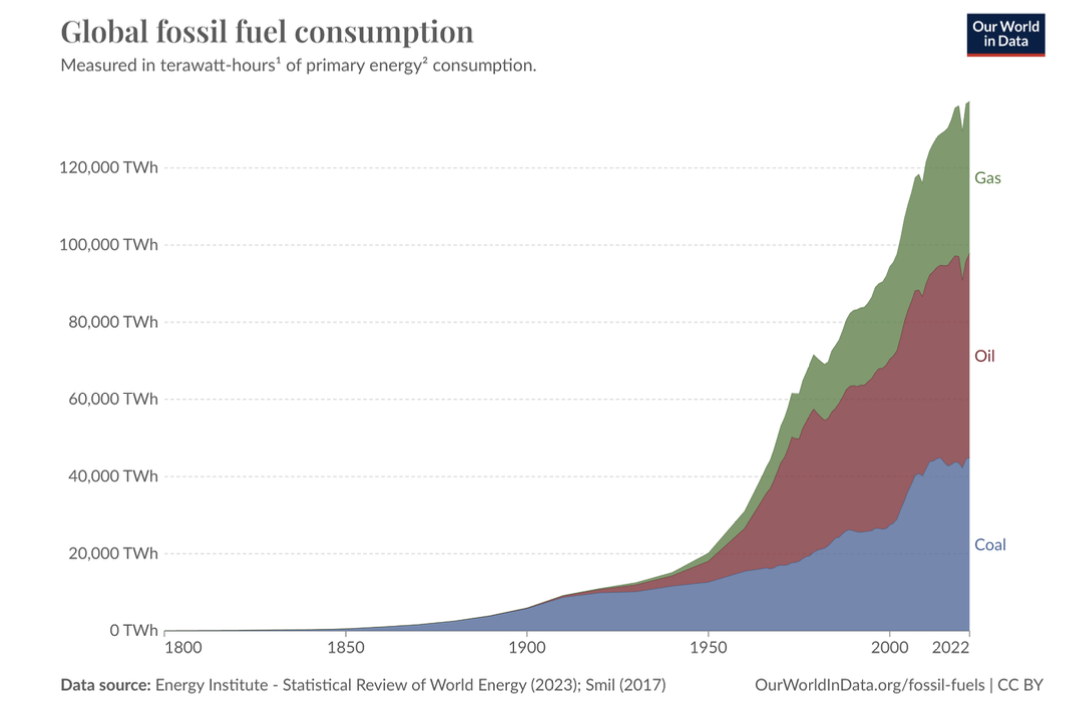

The concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere rose from 275 parts per million (ppm) in 1750 to 415 ppm globally now.8 A major contributor to the drastic increase has been the burning of fossil fuels, where global carbon emissions have significantly increased since 1900. Since 1970, CO2 emissions have increased by about 90%, with emissions from fossil fuel combustion and industrial processes contributing about 78% of the total greenhouse gas emissions increase from 1970 to 2011.9 Globally over 4/5 of all energy produced is made up of coal, oil, or natural gas, all fossil fuels dense with greenhouse gasses. This energy is vital to power our utilities, fuel our vehicles, and provide electricity. Without fossil fuels many of our supply chains and manufacturing processes would not have sufficient power to operate.

3. Past and current attempts to mitigate or solve the problem

3.1 Economic Theory

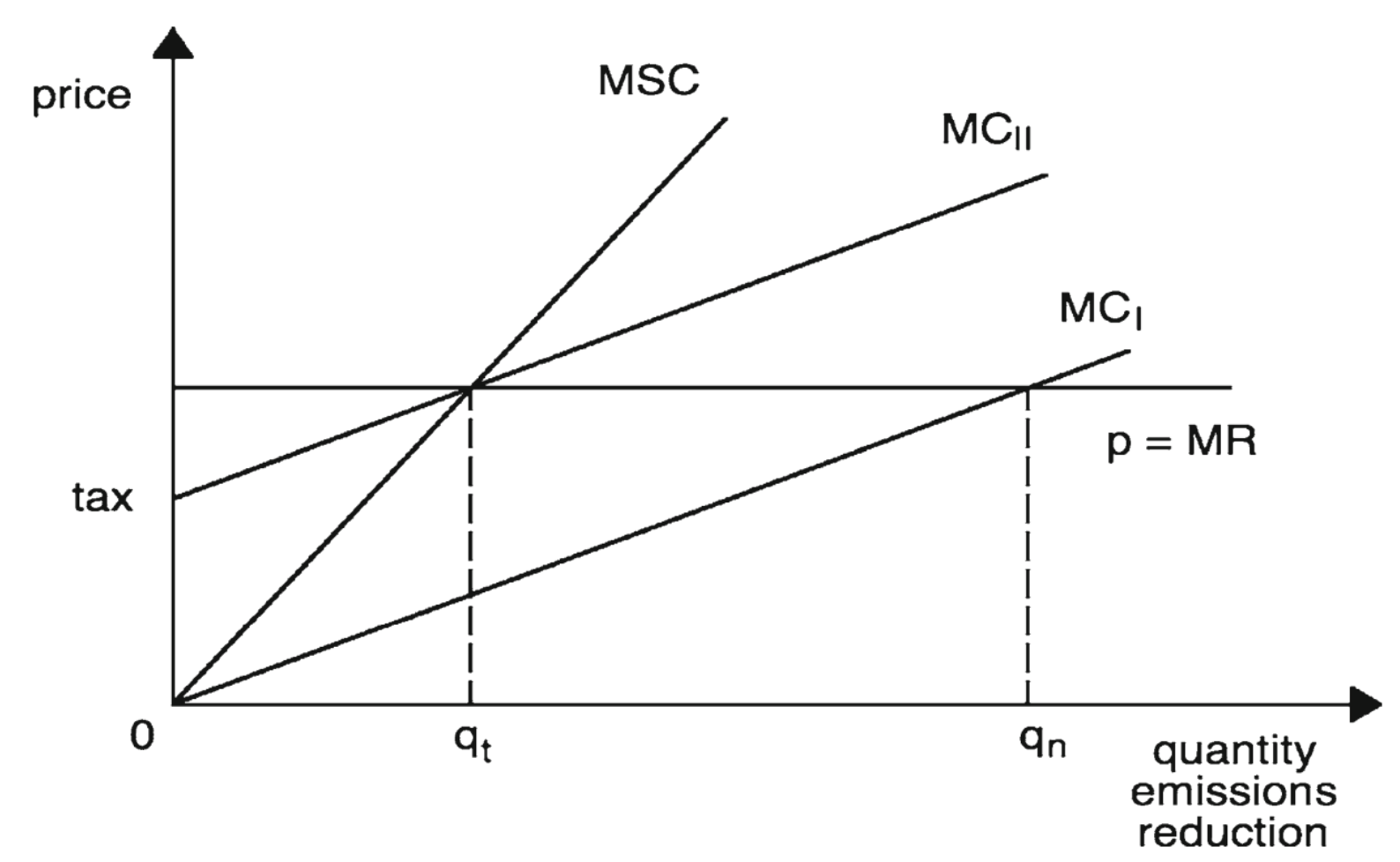

Establishing incentives and economic drivers to reduce negative environmental impacts from market activities has been studied for over a century. The concept of an “externality” was first coined by the British economist Alfred Marshall in work, "Principles of Economics," published in 1890. The externality represents an impact external to a market transaction where there are “external” effects. There are 3 main choices of the key policy instruments that have been developed for the control of externalities: taxes, subsidies and marketable permits. The Tax was first developed by another British economist Alftred Pigou in the 1920s. The Pigouvian approach was a way to internalize these external effects. The Pigovian tax, a tax equal to the negative externality so the costs are balanced. This was one of the first times negative environmental impacts have been flagged by economists and policy makers. From an economic point of view the issue is clear, in a competitive market, firms with free access to environmental resources will continue to engage in polluting activities until the marginal return of their production is 7 zero.10 Because historically there was no cost associated with pollution, these firms would continue to produce until other costs reduced their margin return for production. An effective policy would generate a price equivalent to the cost of pollution and force firms to internalize these social/external costs.

In the 1960s Robert Coase developed his theory of Coasian Trading and social costs. This removes transaction costs and if two parties trade based on their own incurred externalities, they would eventually reach the “Pareto Efficient” outcome. A common example being property rights, as the two parties would be able to reach an optimal price without government intervention. While this is an interesting theory it is hard to put into practice in the complex system of businesses and our natural environment. A pair of Canadian and American economists, John Dales and Tommy Crocker expanded on this idea of diluting trading costs with their method to control pollution in the form of permit markets. A permit is an allowance for emissions and firms would be able to trade permits at their leisure. Through further analysis and models it was revealed that this would lead to lower emissions reductions cost and provide forward thinking firms a reward for reducing past the standards, as other high emitting firms would have to purchase permits from them.

3.2 Policy

The 1970s spurred by the Earth Day movement was a great decade for climate action. Much of the basic policy needed to protect our environment was enacted, such as creation of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), Endangered Species Act, Natural Forest Management Act, Marine Mammal Protection Act, and the creation of the EPA. Most impactful was the Clean Air Act, which resulted in a major shift in the federal government's role in air pollution control. This legislation authorized the development of comprehensive federal and state regulations to limit emissions from both stationary (industrial) sources and mobile sources.11 Later in 1990 this was amended in “Title V” of the 1990 federal Clean Air Act Amendments by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to establish a national, operating permit program. This was one of the first uses of permit markets as these market structures were getting a lot of attention due to one major advantage, the marketable permit approach gives the environmental authority direct control over the quantity of emissions.10 As permit trading mechanisms proved their effectiveness, frameworks in the UN began to develop. The most groundbreaking was the Kyoto Protocol, which sets binding emission reduction targets for 37 industrialized countries and economies in transition and the European Union. Overall, these targets add up to an average 5 per cent emission reduction compared to 1990 levels over the five year period 2008–2012 (the first commitment period).12 This was the first international emissions trading system, and remains revolutionary to this day, as very few international markets exist. Over the following two decades smaller emissions trading schemes popped up across the globe. Their true effectiveness has yet to be fully revealed due to lack of adoption in major emitting countries such as the US.

4. Analysis of current situation

Although the daunting number of anthropogenic carbon emissions continues to rise, with it are those determined to decrease our reliance on fossil fuels and high emitting behaviors. Most notably in 2015 the UN released the Paris Agreement, which was adopted by 196 parties and is a strict 5 year cycled plan to reduce global temperature rise to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change. Additionally just this March the SEC issued a final rule that requires registrants to provide comprehensive climate disclosures in their annual reports and registration statements. These requirements significantly expand climate-related disclosures and the need for developed reporting capabilities. As shareholders have access to published records of companies environmental impacts they can demand lower emissions as this can have serious business risks as well. With all of these disclosure requirements and targets, there is an increasing need for quality market mechanisms and policy adjustments to funnel climate related funds to positive projects. The concept of “carbon pricing” has continued to gain popularity as an attractive approach. Carbon pricing works by capturing the external costs of emitting carbon - i.e. the costs that the public pays, such as loss of property due to rising sea levels, the damage to crops caused by changing rainfall patterns, or the health care costs associated with heat waves and droughts - and placing that cost back at its source.13 This can have many benefits including further 9 investment and innovations with generated revenues from carbon policy. The two main market mechanisms are a carbon tax and carbon cap-and-trade. The goal of carbon taxes or any carbon pricing mechanism is to cost effectively reduce emissions and drive innovation from businesses and consumers to change behavior to avoid the new imposed costs of their environmental impacts. Additionally another advantage of carbon taxes is that they can generate new revenues that can be used towards green projects. A 2017 study estimates a tax of $49 per metric ton of carbon dioxide could raise about $2.2 trillion in net revenues over 10 years from 2019 to 2028. 14 A tax on emissions in Great Britain, introduced in 2013, has led to the proportion of electricity generated from coal falling from 40% to 3% over six years, according to research led by UCL.15 While the carbon tax is an attractive option for policy makers to implement, it can be hard to determine what level to tax at, as many models derive vastly different numbers. The alternative policy instrument is the carbon cap-and-trade model, which aims to set a “cap” or limit on the total number of emissions and allocate allowance credits that companies can trade amongst themselves. This allows the policymaker to set climate targets and companies to have agency to trade and emit at a level that makes sense for them. In California for example, The Air Resource Board set their cap to deliver an overall 15% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and set a statewide limit on sources responsible for 85 percent of California’s GHG emissions.16 There are two ways permits can be allocated once the cap has been set, either for free or through an auction. The advantage of auctioning allowances—rather than giving them away for free—is that resulting revenues can be used to reduce other taxes that act as a drag on income or investment. This can be the most efficient option as it minimizes net cost to the economy. There are two types of carbon cap-and-trade markets. First is the regulatory or compliance market. These are established by governments or multilateral regimes. The other type of market is the voluntary carbon market (VCM). The VCM allows companies, non-profit organizations, governments, and individuals to buy and sell carbon offset credits. The EU ETS is one of the largest multinational carbon markets today. It was established in 2005 and covers over 45% of the EU's carbon emissions.17 Currently, the EU is in Phase 4 of trading where the overall number of emission allowances will decrease at an annual rate of 2.2% from 2021 onwards, compared to 1.74% in the period 2013-2020. The reduction rate is in line with the 2030 target of at least 40% cuts in EU greenhouse gas emissions.18 The expected growth of carbon markets over the next decade is massive. As more and more industries are subject to its regulation, there is an expected domino effect. As one industry is forced to comply, it will push its peers and competitors to face the same rules. Additionally with the new border regulations such as Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) many countries will opt for manufacturers to pay domestic fees as opposed to international tariffs. The VCM is also expected to have huge growth over the next few decades. Boston Consulting Group projects the market to reach between $10 billion and $40 billion, while McKinsey projects $50 billion in 2030, and Morgan Stanley even estimates up to about $100 billion in 2030 and around $250 billion by 2050.19,20,21 The voluntary carbon market can support a wider range of projects that can benefit local communities as well. These projects can include renewable energy, industrial gas capture, energy efficiency, forestry initiatives 10 (avoiding deforestation), clean water, regenerative agriculture, wind power, biogas, oil recycling, solar power, water filters, ocean cleanup, and many more. As the international global targets set by the UN and other major international alliances, we can expect more growth and participation. Today, almost a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions (23%) are now covered by 73 instruments.22 If we continue on this trend soon all emissions will be accounted for and companies and industries will be held liable for their impact on the environment.

5. Proposal

As we continue to uncover the anthropogenic impacts of humans it is important to recognize our damages and take action. We must understand that our GHG emissions are having drastic effects on our environment and societies. It is important to understand, calculate, measure, and reduce these impacts to the best of our ability and extend our time horizon beyond next quarters earnings. This can be done with the social cost of carbon, which measures damages associated with a project including changes in net agricultural productivity, human health, property damages from increased flood risk, and changes in energy system costs, such as reduced costs for heating and increased costs for air conditioning.23 We must understand the full impacts of our decision making as it relates to all aspects of our environment, social, and economic systems. Currently most people make simple economic decisions, but as we begin to realize the importance of sustainability, hopefully everyone will consider environmental and social damages prior to a project. In the future as we see more mature frameworks and advanced methodologies for understanding these impacts, we should also see higher transparency and communication to all stakeholders. For example, a company or entity that is currently emitting a large amount of CO2 reports on their emissions, and regularly updates its stakeholders on the work that it is doing to reduce them. It is important to note that we are all on the same team in regards to climate action. In addition this should be communicated to consumers as well. Market demand is driven by consumers and it can be a powerful economic driver. Climate impacts should not be hidden from consumers, it should be prominently displayed on all packaging, “this product emits X tons of CO2” and consumers can make the choice for themselves if that is something they want to purchase. Just as price can be a deterrent, so should environmental impacts. Beyond just communication there needs to be stronger systems in place for policy. There are some quality international policy agreements such the Paris Agreement and others, but there needs to be more cooperation between countries. It should be clear that there is a necessity for some form of carbon pricing or policy, and world leaders should step up and develop this as there are financial incentives. We need to address our global political systems as well as they are not built to make the best decision rather what suits them the best. Carbon pricing mechanisms such as a cap-and-trade can create new revenues and positive feedback loops for businesses and governments to continue to participate. A market based approach also has advantages as it allows the agency of participants to make decisions for themselves and a true price to be revealed. Unfortunately I do not see this policy or marketplace being built in the near future, hence why the VCM has some appeal. We see businesses and individuals voluntarily reducing emissions 11 faster than policy can be built to address it. The projected growth in the VCM is exponential and will reach hundreds of billions of dollars in the next three decades from a valuation of two billion in 2023. With this also comes a need for education. Educating all parties about what is the right thing to do? What emits the most carbon? How can I change my behavior to be more aware of my environmental impact? These questions should not be complex to answer, but they are. We need to fully understand what is causing our negative environmental impacts, and what we can do to mitigate our damages. This comes with a deep analysis of sustainability and its complex systems. It is clear that even over the last half a century sustainability has advanced at a rapid rate, we have developed technologies that nobody thought were possible, until they were developed. This requires more minds working on our more complex and impending problem yet, climate change. With an increased effort we will see new innovations and transformations in the space, and hopefully reductions in our negative environmental impacts.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion there are a few points to highlight.

- United Nations Brundtland Commission defined sustainability as "meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs."

- When developing solutions to address problems as large as climate change it is necessary to use systems thinking to develop positive feedback looks in all parts of the system.

- Global temperatures have risen 1.1 degrees celsius from 1901-2020. This has already impacted our planet and led to record-breaking heat waves on land and in the ocean, drenching rains, severe floods, multiyear-long droughts, extreme wildfires, and widespread flooding during hurricanes are all becoming more frequent and more intense events.

- Since 1970, CO2 emissions have increased by about 90%, with emissions from fossil fuel combustion and industrial processes contributing about 78% of the total greenhouse gas emissions increase from 1970 to 2011.

- There are 3 main choices of the key policy instruments that have been developed for the control of externalities: taxes, subsidies and marketable permits.

- Carbon pricing works by capturing the external costs of emitting carbon - i.e. the costs that the public pays, such as loss of property due to rising sea levels, the damage to crops caused by changing rainfall patterns, or the health care costs associated with heat waves and droughts - and placing that cost back at its source.

- The alternative policy instrument is the carbon cap-and-trade model, which aims to set a “cap” or limit on the total number of emissions and allocate allowance credits that companies can trade amongst themselves. This allows the policymaker to set climate targets and companies to have agency to trade and emit at a level that makes sense for them.

- We must understand the full impacts of our decision making as it relates to all aspects of our environment, social, and economic systems.

- A market based approach also has advantages as it allows the agency of participants to make decisions for themselves and a true price to be revealed.

- We see businesses and individuals voluntarily reducing emissions faster than policy can be built to address it.

- With an increased effort we will see new innovations and transformations in the space, and hopefully reductions in our negative environmental impacts.